Will I eventually facilitate participatory group processes by inviting no-one to sit in a dark room and breathe with me?

Well, not quite. But after my recent insight about getting more participants by inviting less people, today is all about getting more results by doing less. When you are called to facilitate group processes it is easy to think that you get more effective the harder you work, the more methods you know and use and the more of your wisdom you share. So you squeeze your schedule full of activities, using participatory this-that-and-the-other techniques, some energizer games in between… and your poor participants get exhausted trying to follow your speed and rarely get to finish discussing an interesting thought, because it doesn’t quite fit into your tight time plan. And because everything takes longer than you thought, you decide to shorten the break time (when they could finish the discussions you interrupted).

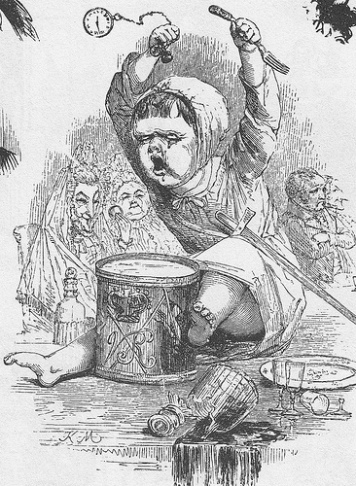

And some of them will think – or even say – “Please, do what you want with us, but stop facilitating us!”. Because they come to think of facilitation as something that is done to them, where they are squeezed into the pre-defined mold of a game-like methods with complicated rules that become so much more important than the serious issues that the group tries to solve. I write about this because I know it – from the perspective of a participant and as an occasional over-facilitator.

I know that over-facilitation often comes from being nervous, trying to do things extra well and the fear of the unexpected, of, even worse, silence. But I also know that from the perspective of the participants it can feel patronizing, like being pushed around and as if my concerns are not taken as seriously as some abstract plan developed beforehand.

If you find yourself in the role of a facilitator and planner of participatory processes and often hear yourself telling your participants to move faster, cutting breaks or engaged discussions short, or spending more time explaining the rules of an activity than actually doing it… go into a dark room alone and do some breathing… And when you come back, have a look at your next workshop plan. Cut the number of activities in half. Plan for longer breaks. When you plan how much time you allot for one activity, don’t ask yourself: “What is the minimum amount of time we would need to do this?” but “What is the amount of time in which we could comfortably do this?” Don’t get too attached to your method but rather stay connected to what the group wants out of this. And allow yourself to change course if you see that you are not getting there.

Some of the most liberating and powerful moments that I have had when facilitating were when I stopped whatever we were doing and admitted: “I have the feeling this is not working for you. I get the sense that XYZ is going on. Is this true? What do you think? I could offer you three different ways of continuing…” And, I must admit, I had some of the most useless, dull and passive aggressive sessions when I knew that things were not working but instead of saying so and asking the group for help, I felt like I had to stick to the plan and just push harder.

Does this ring a bell? I’d love to hear from your experience as over- or zen-facilitator and of your best and worst experiences of “being facilitated”…

Filed under: facilitation, fine-tuning implementation, musings, notes from the field, open questions, Uncategorized | 2 Comments »